It started over soup. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a faculty lunchroom at the Statler Hotel on Cornell’s campus. Economists sat at one table, computer scientists at another. It happened slowly, but over time, the scholars overheard each other’s conversations, recognized common interests and started moving chairs closer.

“I remember conversations about research, how we were looking at similar questions but looking at them differently,” said economist David Easley, the Henry Scarborough Professor of Social Science in the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S). “We realized we each had something to contribute that the other side hadn’t thought of, that could make things better."

And it wasn’t just lunch. Cornell economists and computer scientists kept running into each other, sometimes at the same seminars on campus, other times at Wegmans or at their kids’ soccer games or at coffee shops. Each run-in was another point of connection, often sparking new ideas.

“Ithaca is a small community,” said Jon Kleinberg, the Tisch University Professor of Computer Science and Information Science in the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science (Cornell Bowers CIS). “I think there’s a change in mindset when you think ‘these are all my neighbors.’”

This has a lot to do with social networks, said economist Larry Blume, Distinguished Professor of Arts and Sciences in Economics (A&S) and Associate Dean of Academic Affairs for Cornell Bowers CIS. “We formed a collaboration that still continues by bumping into each other, by being at next tables.”

In one of the earliest of these collaborations, Blume and Easley co-created a course in the early 2000s on decision theory, with computer scientist Joseph Halpern, the Joseph C. Ford Professor of Engineering in the College of Engineering and professor of computer science in Cornell Bowers CIS, also co-authoring a paper.

“I suggested we talk to Jon Kleinberg to ask his help in solving a problem,” Halpern said. “I remember saying that they would enjoy talking to Jon whether or not he could help with our problem.”

The conversations, however casual, led to new research and courses, then to formal collaborations supported by grants. Economists and computer scientists said the connection happened organically, as they found they were working on the same problems – many concerning networks – but from different points of view. Within a few years, Cornell was leading an intellectual movement.

This Cornell collaboration has become influential inside and outside academic circles, impacting tech companies, U.S. government policy and the stock market and bearing fruit in key moments, such as the explosion of social media apps Facebook, Twitter and YouTube in 2005 and 2006; the 2008 financial crisis; and the current rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

In August 2024, Cornell hosted the Economics and AI+ML conference, a step toward a future in which economists and computer scientists are even more closely connected.

"There is so much intellectual overlap,” said Francesca Molinari, the H. T. Warshow and Robert Irving Warshow Professor of Economics (A&S), who first proposed the conference to the Econometric Society.

In a world that’s growing more connected every day, economists and computer scientists say they need to work together. Cornell researchers have thought this way for years, and the rest of the world is catching on.

“When we meet colleagues at other institutions, they all think of Cornell as the place where computer scientists and economists talk to each other,” Kleinberg said.

Getting connected

Today, other universities are trying to catch up, said Éva Tardos, the Jacob Gould Schurman Professor of Computer Science in Cornell Bowers CIS, but Cornell has a long head start. Part of it is the advantage of being in a small town, “locally isolated.”

And part of it, she said, is “that first special year.”

In 2005, a group of computer scientists and social scientists at Cornell formalized their connection by winning a three-year grant from Cornell’s Institute for Social Sciences (ISS; now the Cornell Center for Social Sciences): “Getting Connected: Social Science in the Age of Networks.” With Easley and sociologist Michael Macy as co-primary investigators, about 10 scholars from these various disciplines with a broad, shared interest in networks got a break from teaching and settled into office space in Myron Taylor Hall.

“Networks are an interesting way of connecting disciplines that are unrelated in other ways because the nodes of the network can be all kinds of different things,” said Macy, Distinguished Professor of Arts and Sciences in Sociology (A&S). “The nodes can be people, in sociology. They can be computers in computer science. But they can also be things like airports for figuring out airport route maps. The nodes can even be books.”

“At that time when we were forming, it was incredibly valuable to sit in the same space and to think about these ideas,” said Kleinberg, a member of the “Getting Connected” collaboration.

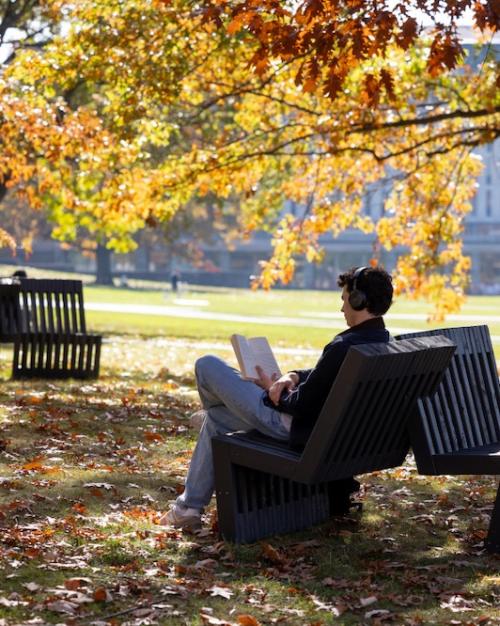

Many papers came out of this grant, and it also made a lasting contribution to the Cornell course catalogue: Networks, a course on how the social, technological and natural worlds are connected.

Co-designed by Kleinberg and Easley, the course presents two big concepts – networks and game theory – and their real-world applications, such as markets and internet search engines. It’s introductory-level but also super-distilled; to create the course, Kleinberg and Easley each pulled the most important ideas out of their graduate level courses and made them accessible to undergraduates, with as little math as possible.

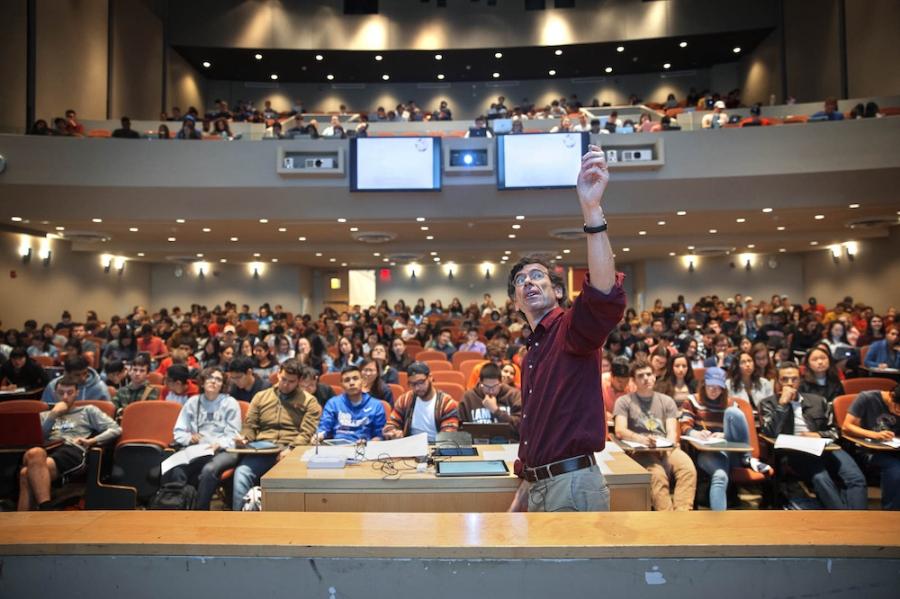

Kleinberg and Easley taught the Networks course, cross-listed in computer science, information science, economics and sociology, in spring 2007. They advertised with posters and expected to get 50 students; 200 signed up.

“Looking back, that was the exact right time to introduce a course like this, because the years before that, you were seeing the creation of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and the iPhone,” Kleinberg said. “Students entering college had spent the last three years in this world that was hyperconnected. We wanted to open that black box and say, ‘you’ve seen the technology that’s in your everyday life – let’s show you some of the ideas behind it.’”

The course is now capped at 700 students, and other professors, including Tardos and Halpern, have taught it. Kleinberg and Easley co-wrote the textbook, “Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning About a Highly Connected World.” There is an online edX course based on the book and taught by Easley, Kleinberg and Tardos, and the idea has been copied by other universities.

“David and Jon’s book on networks has had a major impact on lots of universities, where they’re teaching that course, using that text,” Halpern said.

Cornell did not invent the connection between computer science and economics and other social sciences, Tardos said. But Cornell scholars have done a lot to organize, standardize, expand and entrench the common ground, with the ISS grant and the Networks course as major milestones.

In 2009, the National Science Foundation (NSF) recognized this by funding Cornell to host a workshop on “Research issues at the interface of computer science and economics.”

Complementary skill sets

As collaborations between economists and computer scientists grew and formalized, it became clear: To solve real world problems with a network mindset, researchers in these two disciplines need each other.

It’s a natural marriage, said Molinari, an econometric theorist who studies algorithmic fairness. Economists and computer scientists bring complementary skill sets.

“Economists and statisticians are trained to prove under what theoretical conditions a method works, but not to provide computational approaches to implement the methods,” she said. “Computer scientists have the skill set needed to implement the methods, and bring new insights about their theoretical underpinnings.”

Economics studies humans’ responses to incentives, Easley said, and computer science’s algorithmic designs create incentives that humans respond to. “The two put together create something that actually works.”

In 2015, Blume, Easley, Kleinberg, Tardos and Robert Kleinberg, professor of computer science in Cornell Bowers CIS, wrote in the Journal of Economic Theory about the impacts of computer science on economic theory. New methods of working on economics problems are available by tapping into computer science, they wrote. New issues have arisen in already popular areas of economics, such as learning, decision theory and market design. And new kinds of markets have popped up associated with search engines and social media platforms.

Real-world outcomes

One such market is the online marketplace. Economic exchanges, such as advertisements on search engines, drive online platforms, but designing the algorithms behind these exchanges to accurately represent humans’ financial incentives has been an involved process.

“Google’s ad auction, that’s definitely algorithmic,” Tardos said of the process that determines which ads appear in search results, and in which order. “Humans set up the algorithms but at the speed at which you have to make decisions, millions of ads per minute, humans can’t help. Humans can only control the algorithms. They can’t control the individual decisions.”

Early versions of Google ad auctions, which combine ad purchasers’ motivations with algorithms, failed to consider economic incentives correctly, Tardos said. Some ads were getting lots of clicks but weren’t making much money.

Cornell researchers were among those who caught Google’s ad auction mistake.

“I view this as a place where the incentives and other things economists truly know how to think about, and algorithms get together,” said Tardos. “That’s a killer example of all of us, on both sides, suddenly paying attention to this.”

Economists and computer scientists can also help each other out with equilibrium – or supply and demand – problems.

Think of a grocery store: Even though shoppers and store management balance supply and demand, more or less, every day, it’s very difficult to calculate, Tardos said. So while computer scientists struggle to find a precise computation, economists observe that there’s enough milk on the shelves.

“Economists certainly like using empirical evidence that normally life works out OK,” Tardos said. “Computer scientists would like to understand the conditions that cause the equilibrium to arise.”

“I think the biggest impact has been getting economists to start thinking computationally,” said Halpern, whose research is on reasoning about knowledge and uncertainty and its applications to distributed computing, AI, security and game theory.

Tardos believes the theoretical models developed over the years now effect the way policymakers think – even if indirectly. She finds the words “algorithm” and “incentive” coming more and more into the news and daily conversation. Tech companies like Meta now hire economics graduates along with computer sciences graduates “and they put them in a group so they talk to each other.”

“There’s been a nice flow of ideas back and forth when we think about the network properties in the world and then we bring these ideas to the online domain where you can use them almost in their purest form,” said Jon Kleinberg, whose influential research on networks in the online world is integrated into some of the world’s most ubiquitous online systems – including Google’s search algorithms.

“The physical world is messy and it has lots of stuff going on and you can’t always change things. The digital world often has a flexibility. The design is much more under your control,” he said.

Soon after the financial crisis in late 2008, Jon Kleinberg ran into Larry Blume at Wegmans. “Larry said he was thinking about how financial shocks spread contagiously through networks. We started on a set of projects about how failure is spread.”

Other researchers joined these projects, and the eventual collaboration on this topic included Easley, Tardos and Robert Kleinberg, as well.

“In 2008, the question of whom to bail out had the mantra of ‘too big to fail,’ meaning this bank’s failure would bring down the economy. Part of our research was the shift from ‘too big to fail’ to ‘too connected to fail,’” Jon Kleinberg said. “It’s not so much about bigness, but if you’re a hub in the structure, if I pull you out, the whole structure falls apart.”

Cascading failures through networks also apply to food systems, power grids and pandemics – including the worldwide case in 2020. Collectively, the work in academia has caused a shift in perspective toward recognizing connectivity as an essential component of many real-world problems, Kleinberg said.

While computer scientists have been studying social interactions, Farnoosh Hashemi, a graduate student in the field of information science, has flipped that around, using sociology models to study computer science with Michael Macy, her advisor. She is studying a community of AI bots called Chirper, an analog of Twitter where the users are all bots. “The bots post tweets, called ‘chirps.’ They like, they mention. They do all the things humans do on Twitter,” Macy said. Macy and Hashemi are investigating how the Chirper bots behave, what they talk about, what they think of humans and whether they fall into human tendencies like political polarization.

Each discipline needs the others, Macy said: “The computer scientists aren’t going to know all of the aspects of social interaction in networks, and the sociologists and other social scientists aren’t going to understand AI and deep learning as well as computer scientists do.”

Broadening the exchange

With the rise of AI, this type of interdisciplinary work has become even more vital, and AI is currently Macy’s most pressing project.

“It’s a transformative technology and a good example of why you need collaborations between computer and social scientists and probably other disciplines, as well,” he said. “It is a topic that really does require knowledge coming from very different specialties. This is the work I’m very excited about right now.”

Machine learning is also a rising field in economics, Tardos said, especially where learning and games meet real-world economics, such as in online ad placement. Her current collaboration with Easley – they meet weekly with a Center for Data Science for Enterprise and Society research group – examines what happens when learners interact.

“Algorithms and use of AI have immediate applications in economics,” Molinari said. “I work in econometric theory, so I’m looking at how you would use finite data to evaluate these algorithms and to regulate them.”

In her current research, Molinari is developing statistical tools to test for unfairness in algorithms used, for instance, to grant medical treatment or approve mortgages. These tools will hopefully lead to practical applications in court cases scrutinizing regulations. She presented the research in October at a colloquium of the Department of Computer Science – where Kleinberg is exploring the same topic with MIT economist (and A&S alumnus) Sendhil Mullainathan ’93.

“In particular, we’ve been looking at how human experts in these types of domains interact with tools from AI and machine learning,” Kleinberg said.

“I enjoy talking with computer scientists – interaction, exchange of ideas, good suggestions,” Molinari said. “There is value to being able to statistically test hypotheses corresponding to questions that computer scientists were already asking. Because in real life, you need data to make adjudications. That’s the kind of rich intellectual exchange we have at Cornell.”

The August 2024 Economics and AI+ML conference, co-organized by Molinari and Tardos, brought economists and computer scientists from all over the world to Cornell. The goal was to broaden the interaction between the fields and appeal to even more scholars.

“Machine learning methods are nowadays applied in empirical work in economics, and computer science people together with economists work on analyzing the statistical properties of these methods,” Molinari said. “It’s already happening that these two fields are overlapping, so it was clear the AI specialists from computer science could talk to economists.”

The conference planning committee was made equally of computer scientists and economists, and keynote speakers, all faculty from leading universities, came from both fields. Judging by the number of attendees and the enthusiastic response, the gathering was a huge success, Molinari said. There is overwhelming support for another in two years.

Cornell’s investment more than 20 years ago in “a special mix of people” who shared a vision to do something new has made the university an important hub of economics and computer science collaboration, Molinari said. “What came out of it is extraordinary – teaching, research, conferences. It was so forward looking, and it just keeps going, embracing the future.”

Macy added: “Cornell historically has really celebrated diversity and that has created a seedbed for collaboration.”

“It’s again, a story of networks,” Jon Kleinberg said. “There’s the professional network, there’s the network of who you live next to, there’s the network of whose kids are friends with each other. You superimpose several networks on top of each other and then blend the connections.”